Thanks to ‘KKFlyer’ for sharing his experiences on a recent trip aboard an honest-to-goodness Zeppelin!

Joy Riding in a Zeppelin: Is That Flying, Sailing, or Traveling?

by KKFlyer

First, a bit of history:

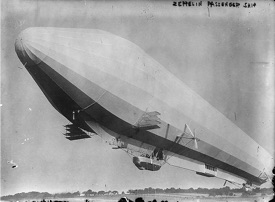

Almost exactly 115 years ago, on the 2nd of July, 1900, the first Zeppelin airship, a lightweight aluminum framework covered with doped fabric and filled with hydrogen gas bags to provide lift, powered by two propellers driven with 14hp engines and steered by a rudder system, took to the skies over Lake Constance in southern Germany, ushering inthe age of practical powered air travel.

The LZ1 at Lake Constance, 2nd July 1900.

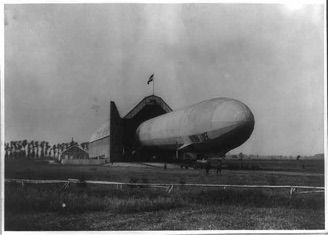

After that first flight, a few years of further improvements to airships brought about the beginning of commercial air service. In 1909, Zeppelin organized what today would be known as a common air carrier, the Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft (DELAG), and began scheduled passenger air service throughout Germany, over 16 years before Lufthansa came into existence in 1926. By 1913, a scheduled service network was being operated between Düsseldorf, Oos (near Baden-Baden), Berlin-Johannisthal, Gotha, Frankfurt am Main, Hamburg, Dresden und Leipzig. Plans to expand the network to other European cities were interrupted only by the outbreak of the First World War.

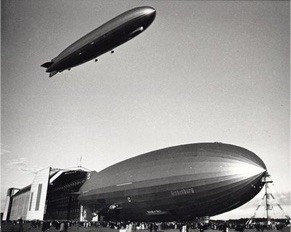

Years later, in 1935, amid moderate commercial success, but under the heavy hand of the National Socialist government, the primary assets of DELAG would be merged into the Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei GmbH (DZR) as an operating partner of Lufthansa and a provider of long-haul airship transport services until the Hindenburg disaster brought an end to long-haul airship services on May 6, 1937. As a legal entity, DZR still exists today, and it again provides Zeppelin-based services, although DZR is no longer affiliated with Lufthansa.

As part of their marketing campaign in the 1930s to promote the in-flight luxury of their airships, Zeppelin used a slogan: Ein Zeppelin fliegt nicht, er fährt…a Zeppelin doesn’t fly, it sails. (for you know-it-alls out there who would argue that the German verb fahren means to travel, you would be right, but in this context, it also describes what ship does when it travels, which is, it sails, cruising on the water). The idea was that with a Zeppelin, one could travel by airship with the same luxury that was until then only afforded to those who traveled by surface ship, except the destination was not limited navigable water—one could in a Zeppelin airship, in principle, travel in luxurious comfort to any point on the planet, quickly and comfortably.

During the golden age of the Zeppelin (ca. 1928 – 1937), traveling long-haul by airplane was typically a noisy, bumpy, tiring affair. Was flying in airplanes adventurous? Yes. Exotic? Absolutely. However, luxurious is not an adjective most would associate with long-haul airplane travel in those days. Transoceanic or even transcontinental flights flew either through or around (rather than over) the weather and they required multiple stops. Even though it was slower, most passengers, even those who were not so price sensitive, often chose to travel in the relative luxury of a passenger ship (or train, in the case of continental travel), where comfortable sleeping accommodations, sumptuous meals, and space to work or relax were preferred over the noise, vibration, and cramped spaces offered by airplanes. Those of you who have been lucky enough to fly in the Ju-52 will recognize that making a long-haul flight in such a machine with multiple stops and slogs through and around bad weather would be grind for all but the most ardent airplane enthusiast. In the 1920s and 1930s, airship travel was something to be contrasted with, not compared to, travel by airplane.

In this context, the Zeppelin-Reederei enjoyed pointing out the relative speed, comfort, and luxury of airship travel. A transatlantic Zeppelin trip was a two day nonstop cruise from Germany to New York (versus a week or more by conventional ship), or a 3-day cruise to Brazil, complete with gourmet meals made from scratch in an on-board kitchen, served on fine china, with small, but comfortable and quiet sleeping berths, a salon with panoramic views of the world passing a few hundred meters below, and even a bar and smoking room (which was no small technical feat, given that the German ships were still flying on highly flammable hydrogen gas in those days). By the mid 1930s, the future was looking bright for airships as a prime technology for luxury long-haul air travel.

A typical (one-way) fare for a transatlantic Zeppelin crossing was about 1000RM, or $400, which seems like a bargain until you consider that in 1937, a typical US factory worker earned about $25-$30 per week, and mid-level executive about $125 per week. So, even for a well-paid senior manager, a round trip on the Zeppeling cost the equivalent of about two months’ pay (that sort of puts the full F fares of Lufthansa or Singapore in perspective, doesn’t it?). In the heyday of the giant airships and airship cruise was an incomparable combination of luxury cruise liner and time-saving express aircraft—if you will, a combination of Concorde and Queen Mary.

Unfortunately, between the disastrous Hindenburg fire in 1937 (which was caught on film precisely because airship travel was so exotic that an airship arrival was considered newsworthy), the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe in 1939, and the development during the war of aircraft with true transatlantic range and service ceilings that allowed overflight of most weather disturbances, the allure of flying across the Atlantic nonstop in hours instead of days spelled for most practical purposes the end of the transport passenger ship, and doomed the airship to a role of coastal reconnaissance, providing advertising space, aerial camera platforms, and joy rides.

Fast forward to today:

Supported by a fleet of four 12-passenger semi-rigid airships (semi-rigid meaning that the new Zeppelins are not quite blimps, but not quite full-blown Zeppelin cruisers, either), the Zeppelin-Reederei GmbH once again offers modest (seasonal) airship rides to the public and private charter services from its home base in Friedrichshafen and select other locations. For fares of approximately 200€ per 30 minutes, passengers can choose rides and routes of 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 minutes, and experience breathtaking panoramic views of the world below from an altitude of about 300m (1000ft) through large, and in two cases opening, windows. At a cruising speed of 40 knots, it is no problem to stick a camera, or even your head, out of the window to get a completely unobstructed view.

View from D-LZZF over northern Switzerland, 29th June 2015. The photographer simply leaned out an open window to take this picture.

In addition to the historical Zeppelin marketing about “sailing”, because they use buoyancy as their primary source of lift to “float” on the air, it is often said of airships that they do not fly, rather, they sail (as in like a ship—an airship). However today as a practical matter, mostly to avoid having to vent expensive helium under certain flight conditions, modern Zeppelins normally operate about 350-400kg overweight and thus depend on aerodynamic forces for about 3%-4% of their lift to maintain a constant altitude. The new Zeppelins are, in normal configuration, technically speaking (very technically), heavier-than-air craft. This overweight condition is compensated during cruise with a slight nose-up attitude, and during takeoff and landing by vectorable (upward-, downward-, and in the case of the tail, also sideways-adjustable) propellers to control speed, direction, and rate of ascent/descent of the ship.

Because the new Zeppelins normally operate a few percent heavier than the air they displace, the Zeppelin-Reederei now argues, in a very narrow-minded and pedantic way, that the new Zeppelins do, in fact, “fly” rather than “sail.” This attitude from Zeppelin is, in this authors view, a sad loss of perspective and further evidence (evidence in addition to the suboptimal design of the Zeppelin NT ships themselves) that Zeppelin has forgotten its own history. But the strategic shortcomings of the Zeppelin product are a topic for another time. Riding in a Zeppelin is a fun and unique travel experience.

“Flying “in a modern Zeppelin:

On June 29 I boarded the Zeppelin NT, D-LZZF, “Baden-Württemberg”, for a scheduled 14:05 departure on a 120-minute round trip at FL 010 and a cruising speed of 40knots IAS. D-LZZF took us from Friedrichshafen to the Rheinfall near Schaffhausen, Switzerland, and back. In command of our flight was Captain Kate Board, a 17-year veteran as an airship aviator, and the world’s only certified female airship captain. Captain Board is a former Virgin Blue (now known as Virgin Australia) pilot, who initially trained as an airship pilot with Virgin Lightships, followed by a stint flying a Zeppelin NT in California with Airship Ventures before she joined the Zeppelin-Reederei a few years ago.

The Rheinfall is a waterfall in northern Switzerland along the River Rhein between the cantons of Schaffhausen and Zurich, and a beautiful natural attraction. In terms of flow volume, the Rheinfall is the second largest in Europe, with a mean annual flow of 373 cubic meters per second (the Sarpsfossen in Norway is the largest, at 577m3/s). In terms of height, at 23 meters (75 feet) the Rheinfall is also the second highest in Europe (the Dettifoss in northeastern Iceland is the highest at about 45 meters (148 feet) high, with another 27-meter drop two kilometers further downstream, and a flow volume of about 193 m3/s). For the technically oriented, one can easily calculate the maximum theoretical power produced by a waterfall by multiplying its flow rate by the specific weight of water and height of the fall. Thus if you could somehow extract 100% of the energy produced by the Rheinfall, you could generate on average about 84 megawatts of power.

After an on-time departure from FDH, we set off to the west, sailing across Lake Constance, over the city of Konstanz, and along the Rhein, taking in lovely views of the surrounding villages and countryside. After about 50 minutes, we reached the Rheinfall, making a slow, circular pass around the fall that afforded spectacular views from multiple directions. One nice thing about the Zeppelin is that the center of the lift force is located several meters above the cabin. Practically, this means that the trim (balance) of the airship is virtually unaffected when all 12 passengers gather one one side or end of the cabin to take in special views, so it is quite easy to move around look out in every direction, including forward, through the open cockpit.

The Zeppelin NT cabin. Seatbelts and sitting down are only required for take-off and landing (and of course upon command of the crew).

After an equally scenic 50-55 minute return flight from the Rheinfall to Friedrichshafen (including a sparkling wine toast celebrating the overflight of the Rheinfall), we made a notably steep but smooth decent back to our start/landing site, and touchdown occurred at precisely 16:05, giving us exactly 120 minutes in the air to enjoy the unique Zeppelin flight (or is it sailing?) experience. For me, the time passed much too quickly, and I hope I can experience another Zeppelin flight again soon.

More information on sailing/flying with Zeppelin and cruise/flight availability can be found here: